Foundation for Rural & Regional Renewal (FRRR)

Cumulative disasters have taken a heavy toll and left local leaders in remote, rural and regional communities feeling “uncertain”, “frustrated”, and “tired/fatigued”, although hopeful, according to a study released today.

Commissioned by the Foundation for Rural & Regional Renewal (FRRR), a charity dedicated to supporting grassroots community groups and not-for-profits in remote, rural and regional Australia, the Heartbeat of Rural Australia survey sheds a light on these often unseen and unheard organisations and shares their firsthand experience of how non-metro communities are faring.

FRRR CEO Natalie Egleton, says that the study is among the first to attempt to quantify the critical role these groups play in remote, rural and regional communities, as well as what needs to change if they are to continue to deliver services that sustain rural communities.

“These organisations are vital to the health, wellbeing and prosperity of these communities. In particular, they provide vital social connections; manage and maintain critical community infrastructure; deliver essential services to community members; and a range of other supports.

“These small groups, most of which are not normally eligible for either government funding or philanthropic support, are the backbone of their communities, with nearly 90 percent of respondents saying they play some kind of economic role. Many are responsible for more than one aspect of life in their community and almost all play a critical cultural or social role.

“What this study really highlighted was that if they were to fold – which some told us could occur without additional support – the communities they serve may well ‘‘wither and die”. At the very least, there would be significant gaps in services, the burden for which would move to government and the private sector,” Ms Egleton explains.

The study highlighted a lack of digital connectivity is significantly hampering rural Australia’s ability to thrive, and to maintain critical social connections.

“Access to digital technology in rural Australia really hasn’t improved in decades. Even where there is connectivity, it is expensive. While external funding often covers the hardware, there is insufficient income to cover the ongoing operational costs such as WIFI access, managing cyber security and training volunteers.”

There were also key issues raised around workforce attraction (including housing availability), mobilisation and infrastructure, which smaller and more remote communities require tailored solutions to, according to Ms Egleton.

While more than half of respondents reported that uncertainty is of greatest concern to them, resulting in “increased general stress / mental health”, by far the most detrimental effect of the pandemic has been the inability to meet with one-another, resulting in isolation, reduced wellbeing, and increased stress – especially for those also recovering from disasters.

The onset of the pandemic weakened the ability of community organisations to play their various roles in the community, at a time when, for many, demand for their services increased. Many – especially organisations with revenue of less than $50,000 – saw significant reductions in income from not being able to run fundraising events and income-generating activities and, in some instances, funders redirecting their support.

“At a community group level, the disruption has been constant, with the effects of cumulative disasters topped off by the pandemic. This has left local communities in a constant state of anxiety and uncertainty.

“It’s also meant that community groups – more than half of whom are made up entirely of volunteers – are being called on to do more, for longer. The reality is that they are not resourced to endure this level of disruption. Yet, in many smaller communities, they simply have had to do it as there is no one else. That is fatiguing; that’s the pure exhaustion that we heard – the effort to keep focusing on your town, your small business community; keeping people connected and supported – especially when there are so few volunteers bearing the load,” notes Ms Egleton.

FRRR is calling for those that are concerned about rural communities to come together to better target support for rural, regional and remote not-for-profits and community groups.

“This report gives us a great opportunity to step back and consider how we can better support and resource these organisations to do what is critical work – and work that only they are really able to do effectively because they are in and of these places. At present, the broader funding mechanisms and policies don’t value these organisations in line with the contributions that they make.

“We are still working through the findings in detail, but it certainly points to an opportunity to come together – philanthropy, government, corporations and individuals – and explore how we can better support these groups for the long-term. We need to take a coordinated approach to removing many structural barriers that are evident in this research if we want rural Australia to prosper,” Ms Egleton explains.

To explore the full report, head to www.frrr.org.au/heartbeat. FRRR has also partnered with Seer Data and Analytics to make the full dataset available online. The data can be cross-referenced with other publicly available data, enabling community groups in particular to better advocate for the support that they need to survive.

FRRR will host two webinars to explore the findings in more detail. The first, focused more on community groups, will be held on Tuesday 30 November, and a session tailored to funders, policy-makers and the broader sector will be held on Wednesday 1 December. Both sessions will begin at 12.30pm AEDT and be held online. Register at www.frrr.org.au/heartbeat.

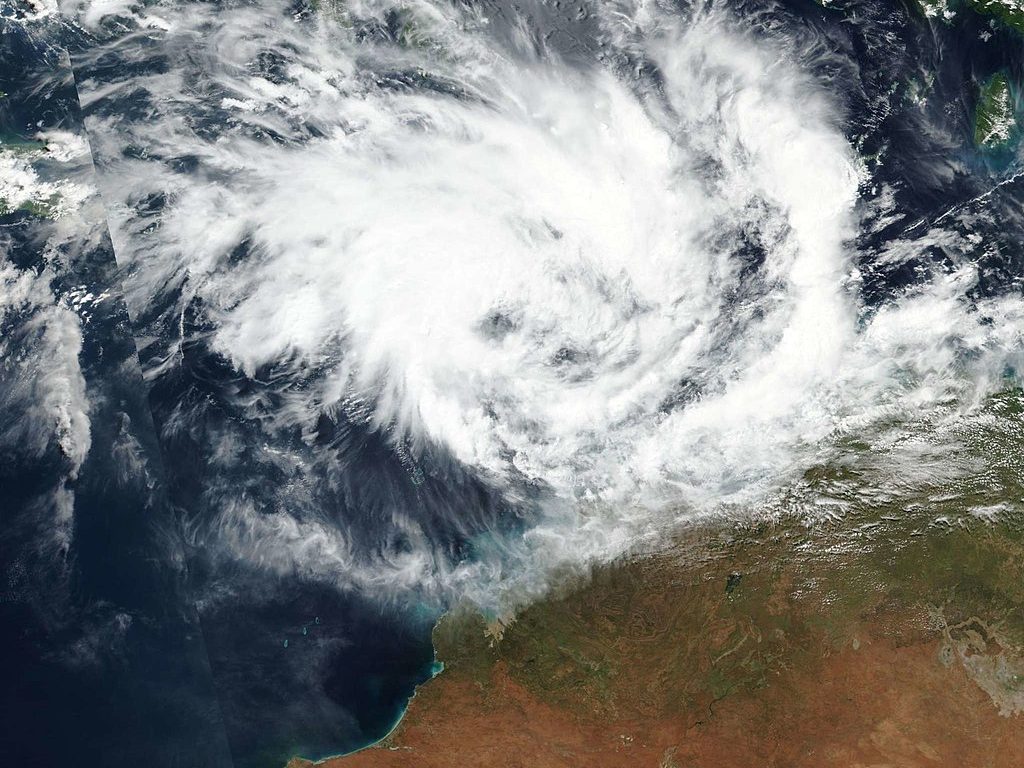

FRRR acknowledges the devastating effects that Cyclone Seroja has had on a number of remote communities across Western Australia.

Natalie Egleton, FRRR’s CEO, said that the Foundation knows recovery for these impacted communities has only just begun, with reconnection of power an immediate priority, and the rebuilding damaged houses, farms and public assets to occur in the months and years ahead.

“We also anticipate that the activities of local community groups, which are so vital to the ongoing fabric of Western Australia’s remote, rural and regional communities, will be significantly impacted. But we also know these groups will play a vital role in supporting their community through the recovery journey.

“FRRR encourages any donors interested in assisting these affected communities to donate to charities registered with the ACNC, and to consider supporting the needs of communities through the medium-long term recovery journey, in addition to their more immediate needs,” Ms Egleton said.

FRRR has a long history of assisting communities to recover from disasters. We have facilitated support to communities recovering from the recent NSW floods; the 2019-20 Black Summer bushfires; 2019 North Queensland floods; Cyclones Debbie (2017), Oswald (2013), Yasi (2011) and Larry (2006); the 2013 Blue Mountains bushfires; the Victorian Black Saturday bushfires of 2009; and ongoing droughts; and to those places preparing for future disaster events.

“More frequent and intense climate disasters means that Australia needs to be proactive in how we fund communities to assist with their preparedness activities, and to have funds available to support them through the medium to long term aftermath of a disaster.” Ms Egleton explained.

Any funds donated to FRRR to support WA communities affected by Cyclone Seroja will be allocated through the following two key mechanisms:

- FRRR’s Strengthening Rural Communities program, which is open all year round, and assessed quarterly. Grants of up to $10,000 will be distributed; OR

- FRRR’s Disaster Resilience and Recovery Fund (DRRF). The DRRF was initiated in August 2019, in response to an increasing frequency of disasters. FRRR wanted to ensure it had a corpus of funds invested, so that it can provide some support to disaster impacted communities whether they’re large or small, in the public eye for a long time or swallowed by other events, or are well-supported philanthropically, or not. Donations made to FRRR’s DRRF are pooled and invested, making it a gift that keeps giving, with earnings drawn off every year to be distributed to communities impacted by disaster through grants in programs such as Strengthening Rural Communities. The DRRF currently holds over $4M, which is invested. FRRR will provide support to community groups recovering from the impacts of the cyclone over the coming years, by applying a portion of the earnings from this fund.

FRRR welcomes donations to either of these mechanisms. All donations over $2 are tax deductible in Australia.

Beyond FRRR, the Foundation encourages everyone to consider the impact that this cyclone has had on many individuals and communities across WA, and consider giving to a DGR-1 endorsed ACNC registered charity, which can support individuals and their communities through the recovery journey.

For more information, contact Sarah Matthee, FRRR’s General Manager, Partnerships and Services.

By Natalie Egleton, CEO

Over the past month, I’ve had dozens of conversations with community leaders, local, state and commonwealth governments, philanthropic foundations, and corporate partners, that have all circled around the question of disaster resilience and best practice giving. I’m encouraged by the growing sentiment that recognises the increasing frequency and severity of disasters, yet also see a pressing need to shift our approaches to funding disasters as one-off events.

The floods that have devastated so many areas across NSW and parts of Queensland this month are yet another in a series of disasters that rural communities have had to face in the past year. Many of those communities have experienced prolonged drought, bushfires, minor flooding, and now catastrophic flooding. For these communities, the rebuild, recovery, and long-term renewal will call on yet more reserves of social capital. Support will be needed that doesn’t compartmentalise their various disaster impacts and which acknowledges the deeply fatiguing and depleting effects of successive disasters on people, communities, and local service systems.

At FRRR, we view disasters as environmental shocks that remote, rural, regional communities regularly experience. We know they are inevitable and increasing in frequency and severity; what makes them complex is not knowing when they will occur, where, or the severity and nature of their impact.

Recovery and preparedness are only as strong as the social ties, quality of community infrastructure, depth and breadth of skills and networks, cultural knowledge, and the health of local service systems, non-profits, and community groups.

That’s why investing in social capital – preparing for future disasters and adapting to changing conditions after a disaster – underpin our ongoing work outside of disasters. Mitigation and making advances through technology is vital, but only effective when people within communities – those who will act first and drive recovery and preparedness – are invested in.

Our approach is to provide support where there are gaps or quick responses are needed in the short term, however we focus the majority of funds on the medium-to-long term recovery and future preparedness efforts of rural communities. Funding medium to long-term recovery ensures that resources are available to help communities when they are ready, beyond their immediate needs that arise during the emergency.

Adapting and evolving

In operational terms, FRRR has a standing disaster philanthropy model that we scale when a major disaster occurs. Each year, with support from hundreds of donor partners, we provide grants and capacity support to around 500 hundred remote, rural and regional communities across the country via almost 800 grants. This reach gives us a good footprint and connection points that we can naturally tap into when disasters occur.

Right now, we have almost 1,500 active grants in place for diverse projects in remote, rural, regional communities nationally; around 40% of these are supporting community-led recovery and resilience initiatives.

When the 2019-20 bushfires hit FRRR had to scale our processes very quickly. We expanded existing grants programs that have a national footprint, as well as brokered funds management for corporate partners to support short-term recovery.

In the space of a month, FRRR went from having about 700 donors to 30,000 donors. We had to ensure our systems could cope and we needed to scale up our communications and finance management resourcing. At the same time, we were engaging in working groups and forums with Governments, philanthropy, and connecting with fire-affected communities where we had active grants and relationships.

When COVID-19 hit, our biggest challenge, aside from looking after our people, was adjusting our community engagement approaches.

While regional Australia is great at working remotely, working on recovery, trying to engage with largely volunteer-led community groups and not-for-profits is really done best in person.

Understanding the local context can be done remotely but it’s not ideal. We also found that as restrictions came into place, a lot of community groups went to ground.

We knew there would be significant impacts from COVID-19 on recovery from the 2019-20 bushfires because the lockdowns would essentially stall social recovery processes, which are most effective when people come together physically, to process and heal.

One of our big, but unsurprising observations during COVID was the gaping hole in digital inclusion – equitable access to stable telecommunications, low levels of digital connectivity in households, and low digital literacy in what are largely ageing populations. In the Snowy Valleys for example, we learnt that 24% of people didn’t have an internet connection at home. In Tasmania, connectivity is inconsistent and communities very isolated.

At the same time, we were seeing independent news publications falling over and rural communities were becoming even more isolated.

The shocks and disruptions just kept coming and the readiness wasn’t there. And then, large parts of NSW were impacted by once-in-a-century floods.

We hear a lot about needing to increase resilience and I am of the firm view that that is coming from the wrong angle. There is an abundance of resilience, but only so much that any strong community can absorb and bounce forward from.

Embedding disasters in regional development practice

The past year has proven the repeated warnings of many. The frequency and severity of natural disasters will cost society, economies, biodiversity, and liveability. We need to do things differently.

In our work partnering with a community in NSW focussing on their non-profit sector capacity building before the 2019/20 bushfires, it was clear that those organisations and community leaders were more ready to respond to the recovery process and opportunities it presented. These same communities are now facing an unimaginable clean up and recovery from flooding. Our role is to be there, offer patience, continuity, flexibility, and agility to move how and when the community is ready with fit-for-purpose funding and resourcing support. The critical piece here is that when we do this work between disasters, reserves of social capital can be replenished and expanded. Communities are more able to engage with mitigation and do essential future-focussed work to strengthen their response to risk and climate change.

Innovation and renewal – applying learnings to support flood-impacted communities

Since the bushfires, we have reviewed and adjusted our approach to funding the core operating costs of the community groups that are so essential to the fabric and vitality of remote, rural and regional communities.

With the funding model of our national small grants programs being relatively unpredictable and dependent on donations from our partners, it is difficult for FRRR to commit to resourcing beyond one-off grants that seed and strengthen locally led projects.

However, throughout the pandemic, the FRRR Board recognised that the depletion of fundraising revenue, volunteer capacity, and local sponsorships, coupled with increased vulnerability and successive disasters, presents a serious threat to the survival of community groups and local not-for-profits. We recognise this as being critical at this point in time, so we will support core overhead costs until the picture changes. It will still be one-off funding but will help to keep the lights on and people working on key issues, while communities and organisations adapt and evolve through the recovery.

This approach translates to better practice for disaster philanthropy overall.

Given what is unfolding in NSW and Queensland at the moment, it is time that we stop looking at disasters as one-off events and view disasters as a constant. This means that we need to invest in underlying capacity and capability at the community level.

The new National Resilience, Relief & Recovery Agency, along with several State Agencies, are now modelled through an all-hazards lens and hopefully the policy and funding settings will follow. Philanthropy can then play a meaningful role beyond responding to successive crises.

It’s certainly where we are focussing more and more of our efforts, and we welcome more conversation on this.