Foundation for Rural & Regional Renewal (FRRR)

Having worked at a community level for 5 years now, most recently as a Program Coordinator and Community Development Officer for Blackall Tambo Regional Council, Jaimee-Lee Prow has experienced first-hand the generosity and good intentions that relief agencies have when it comes to drought in remote, rural, and regional communities. However, these good intentions often don’t translate into practical and accessible support at a grassroots level. Here she shares her story.

To paint a picture of what I mean, I’ll explain a bit about what our experience has been with relief agencies within the central western Queensland drought space. Off the top of my head, I can name at least 20 organisations that offer much the same kind of assistance. This overlapping service provision is driving a state of competitiveness among these organisations and, from a community perspective, has led to a matrix of issues that prevent community groups from taking them up on their offers of assistance. This, on top of a disconnect at a community level, has meant that these relief organisations are actually hindering themselves from reaching the goals that they set out to achieve.

We rural people are a stoic breed. This over-supply of relief support has led to a lot of miscommunication, confusion, and apprehension, resulting in people abstaining from seeking assistance. Or else people become overwhelmingly confused about how to navigate the many systems with most deeming it as an added stress that they simply don’t need. Another familiar scenario is that of individuals, community groups and local-not-for-profits who don’t apply for assistance through one organisation because they’ve already applied for similar assistance through another organisation, and they fear that it will be seen as ‘double dipping’.

Beyond the confusion and burdensome processes, rural communities often feel that these relief agencies fail to properly consider the demographic that they’re dealing with. A large portion of our graziers, primary producers, small business owners and community members are over the age of 65 years with many of them either being extremely hesitant about social media or else completely oblivious to it. Yet, many of these relief organisations use social media as their main tool for promotion and one of their primary platforms for getting information out there. It’s also common that applications for grants will exist predominantly online and even requests for assistance are virtual. As a result, a large portion of our drought impacted population are missing out on the valuable financial assistance offered by the relief agencies. So, a word of advice – this generation still rely on good old-fashioned word of mouth, and mainly prefer to trust “the local bloke”.

Charities, not for profits and non-government organisations can take action to shift from their traditional roles as relief agencies and move towards becoming partners who walk in lockstep with resilient and prepared communities. These relief agencies are, of course, well-meaning but most, if not all of them, are based outside of our region. Some of them even have a strictly virtual presence. Which is why, despite the obvious devastation of drought that surrounds us, they often walk away scratching their heads at the low levels of relief uptake after briefly popping up in our communities. The lack of local coordination and sharing of information on the ground is, ultimately, failing our rural communities.

So, how do we fix the problem?

The solutions aren’t necessarily innovative or complex. In fact, they’re quite simple. Below is a list of steps that relief agencies can take to provide effective support to our drought effected communities:

Step one: listen to the locals

As mentioned in the Red Cross Drought Resilience discussion paper, projects and program delivery from organisations need to be locally focused to meet the needs of the region they are working with. When it comes to providing assistance for our communities, blanket approaches simply don’t work and a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution doesn’t exist.

Step two: we need more than just a plan for the future

We are really at a critical point within the community drought recovery process where we need to keep the momentum going and continue to create or maintain partnerships. Within my local community. I have recognised a shift away from the initial panic and knee jerk reactions to the disaster. Local individuals, groups, businesses, and farms are now ready to accept and explore actions they can take to prepare for future drought- something that wasn’t possible in the initial stages of drought response.

Our initial response was to flood funds upon our drought impacted communities. And this was evident in the amount of overlapping we saw in service provision from our relief agencies. Don’t get me wrong, to a degree we certainly needed it. But what we are starting to see or recognise now is that drought funding is starting to dry up, and services are beginning to wind back in our rural communities. This imbalance between community readiness and resources, and the funding now available is a major concern moving forward. In the disaster recovery and planning phase, we need the resources now more than ever to be ready for next time.

Step three: simple applications and greater flexibility

We need to ensure application processes are simplified and easy to access. This will benefit all sections of the community but is crucial if organisations want their programs to be accessible to applicants aged 65+. Secondly, because each region is different, the criteria grants need to be made more flexible so that projects can be locally defined by the communities themselves and can be used to support a cross section of activities such as infrastructure, events, training, capacity building and network development.

Step four: recognition of the role that local organisations play

Local organisations are the backbone of remote, rural, and regional communities. Therefore, programs need to be modelled around their goals and needs. In order for partnerships to be successful and meaningful to our communities, agencies must be personable within the community, and the program itself must be driven by the community that the agency is working with.

During my time working at Blackall Tambo Regional Council, I have worked closely with FRRR on a number of drought resilience initiatives. FRRR have championed solutions that have been led by our community and that are driven by the needs and abilities of those living in our region. I believe that this approach to disaster recovery is the way of the future.

Step five: events and projects should be led by trusted locals

This is the valuable way to connect, respond, recover and plan ahead. While some are of the belief that the community barbecue or the local arts and cultural workshop are a band-aid solution to relieving the impacts of drought, those from rural communities would actually beg to differ. We come from significantly isolated areas. These types of community events, particularly during drought, are a necessity for creating touchpoints, social check ins, networking opportunities, and they keep our communities connected.

Some of the most brilliant ideas for future proofing and planning are sprouted through general chitchat amongst like-minded people at these types of events. We are already seeing some relief organisations which have come into our region, begin to recognise these events and spaces as the perfect platform for informal networking and building a rapport with our community members. As a result, partnerships have become stronger, and we find that these organisations who take these extra steps have a better understanding of our community’s needs which results in a greater uptake of their services.

Step six: continued government and philanthropic support

As I’ve already mentioned, it’s crucial that relief agencies don’t simply pull the plug and let funding dry up. Our rural communities are now more than ready than ever to prepare and build resilient regions through planning and projects. We just need the continued commitment to fund and provide resources.

Step seven: build local champions

As an NFP, charity and non-government organisation you should be an active collaborator, but you should essentially be led by locals. Start building your local champions in the communities you were working with. They will be your best investment.

Finally, I’ll finish with something I heard once that I believe perfectly sums up the attitude we must approach the future with if we’re going to continue to build prepared and resilient communities: “You don’t need to be strong to survive a bad situation. You just need a plan.”

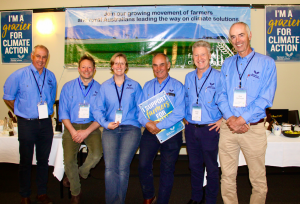

Farmers for Climate Action (FCA) is a growing organisation that has made it their priority to spread the word amongst those in agriculture that it’s time to act on climate change.

In a sector steeped in custom, tradition and routine, being a champion for change can sometimes prove challenging. FCA’s savvy approach to facilitating change and the traction they’ve gained in a relatively short time indicates that there are many that share their desire to take action. They have spent the last few years building their foundations and growing their programs, which not only inform and educate, but are facilitating lasting change at a grassroots level.

One such program is the Climate-Smart Fellowship, which was recently delivered to more than 50 forward-thinking farmers in Tasmania, Queensland and Victoria. It entails training on critical subjects such as climate smart agriculture, climate change science and local capacity building. The program featured experts presenting topis including on-farm change, renewable energy, regenerative agriculture, communications and building advocacy in their local region. These new agents of change were then encouraged to take these learnings into their local area through events, community outreach and calls to action.

By adopting this kind of approach, FCA has expanded their network exponentially, teaching and inspiring a growing nationwide network of farmers. These producers are now equipped with the skills, support and resources – and no doubt the passion – to employ smart farming practises to minimise their impact on the environment.

With FRRR’s support over the past few years, primarily through a Not-For-Profit fundraising account, FCA has grown from a well-intentioned group of dedicated people to a well-funded and structured organisation with a strong foothold in the area of actioning climate change in Australia.

FCA established the account in 2017 to allow them to leverage FRRR’s special tax status to bolster their fundraising whilst they sought to obtain DGR endorsement. In total, $823,340 was raised through the account, thanks to FCA’s focused efforts on crowdfunding appeals, monthly donor programs, corporate donations and various grants.

Recently FCA secured DGR-1 status allowing them to offer their donors tax deductibility, so they no longer need the partnership with FRRR to support their fundraising. However, James Atkinson, Fundraising Manager at FCA, says that the support from FRRR was critical in the success of the organisation.

“Our partnership with FRRR has been crucial in securing new funding relationships, both due to the fundraising account and the strength of our relationship in rural and regional Australia. Several funders reported that they were pleased to hear we had such a close relationship with FRRR.”

James Atkinson, Fundraising Manager at FCA

Natalie Egleton, FRRR CEO, said “The ongoing positive impacts of FCA’s programs in remote, rural and regional Australia is a credit to their commitment and we look forward to continuing to support and amplify FCA’s activities into the future as they go from strength to strength.”

Baranggum Country

The small rural town of Hannaford on the Western Downs in Queensland is battling what would seem to be an endless drought. With a town of just 120 people consisting mostly of primary producers, they have been heavily impacted by an ongoing lack of rain.

Cue the vibrant and dedicated Hannaford Club Inc – a community club founded in 1946, originally to maintain the Hannaford Memorial Hall in honour of the fallen.

These days though, this Club does far more than that. With its dedicated volunteers and committee members, this proud community organisation hosts and runs countless fundraisers both for the town and further afield. From the Hannaford Tennis competition to the Dalby Christian Youth Camp, the seemingly tireless fundraising and support efforts of this Club have, over the years, proven integral to the town’s survival – not just proving their resilience, but also showcasing their indelible ability to prosper.

A big part of the Hannaford Club’s fundraising efforts involve catering for all these events, which often draw crowds in the hundreds. Unfortunately, outdated and slow catering equipment was increasing volunteer workloads, as well as service time for getting food to patrons. The Club identified that an upgrade was sorely needed.

With a grant from FRRR’s Strengthening Rural Communities program, funded by donor’s Dr George Jacobs and Dr Janice Hirshorn, the Club has been successful in obtaining new equipment.

The funds were used to purchase a high-volume, gas-operated deep oil fryer, an ambient cake display cabinet, and a high-volume gas-operated BBQ. With the ever-increasing patronage at their events, this improved equipment will enable the Club to continue to support not just events hosted by them, but it will benefit the wider region, as people are welcome to borrow the equipment for their own fundraising events.

Annie Hubbard from the Hannaford Club said that the Hannaford Campdraft held in May 2021 was their first catered fundraiser since the COVID lockdowns began.

“We were so proud to be able to more than adequately cater for a huge crowd of over 300 people quickly and efficiently. The new equipment was of great use – the volunteer catering committee and all attendees benefited significantly, and it is so very much appreciated!”

Iningai Country

For years, Central Western Queensland has been heavily impacted by the economic, environmental, and social effects of a prolonged drought. Topology, a grassroots community arts organisation, decided to tackle these impacts and empower their communities with music and performance.

Topology’s goal is to build the creative capacity of their participants and to help increase social connectedness through much needed community-based and intergenerational events. And that’s exactly what they achieved when they launched Top Up Central Western Queensland. This initiative consisted of a series of 12 workshops and a four-day creative bootcamp that culminated in a free community performance in Longreach, which was attended by 2,000 people.

Through our Tackling Tough Times Together program, Topology received a grant of $10,000, funded by the Tim Fairfax Family Foundation, as well as separate funding through the Building Better Regions Fund. This money paid the local artists who hosted workshops, as well as covering venue hire and event costs.

The Topology team said, “One of the things we are most proud of is seeing people of all ages, some with no previous experience of the arts, learn about their own potential for creativity – and to perform in public a new piece they have written and contributed to themselves. The feelings of self-accomplishment and pride achieved by the participants is a real and invaluable outcome of this program.”

The program was also the catalyst for Topology consulting with the community on the development of a Regional Creative Hub (RCH). This hub will have lasting impacts for local communities, as it will help to support and upskill rural creative practitioners and community arts organisations.

Top Up Central Western Queensland empowered, educated, and inspired the community to create, perform and tell their stories, while celebrating their community. It was a much-needed reminder of their resilience and their ability to thrive through tough times together.

This mini-documentary showcases some of the highlights from Topology’s Creative Boot Camp which took place in Longreach, QLD in September 2019. This video features a number of young musicians from across the Central Western QLD region alongside Topology’s Creative Tutors.

The town of Stanthorpe, in Queensland is no stranger to hardship. After years of drought and bushfires, the community was already feeling the pressure when COVID-19 hit. Like many rural, remote, and regional towns, social isolation is a huge issue, now more than ever with strict rules on social interactions and gatherings. These restrictions made it particularly difficult for visitors to come to the area and spend money at local businesses, putting more financial pressure on the community already feeling the effects of years of severe drought. It was so bad, the town was even trucking in water for residents.

The Granite Belt Art and Craft Train Inc (GBART) was determined to push through all these challenges. GBART’s purpose is to support community wellbeing and economic diversity through improving the Granite Belt’s cultural vibrancy and identity. The region stretches from the Great Dividing Range in Queensland all the way to the New England region of New South Wales.

Thanks to a $20,000 Tackling Tough Times Together (TTTT) grant, GBART was able to hold the highly anticipated annual culture and tourism event, Open Studio, which took place over three days and attracted approximately 4,000 visitors.

Open Studio involved hands on workshops, classes and demonstrations, while also engaging with Australian art and craft in active, inclusive ways. The events were hosted at 27 different venues, including wineries that saw visitors stopping to taste, shop and eat.

The TTTT grant allowed GBART to fund a range of supporting resources such as the training and up-skilling of volunteers, purchasing office and IT equipment, venue hire, advertising and marketing material, COVID-19 cleaning equipment and training, plus salaries for an event coordinator, administration support, and a media consultant.

The event was a major success, bringing the community together and engaging visitors from surrounding towns. Best of all, there were little to no changes needed to their original plan. Event organisers said they were “proud of the venues, the accommodation and hospitality businesses that supported the artisans and hosted them in their venues, and we are proud of the artisans who provided the engagement that brought everyone here.”

In the remote locality of Clarke Creek in Queensland’s Isaac Region, a community of 320 people have been doing it tough in recent years. In March 2017 Tropical Cyclone Debbie and flash flooding devastated the area, and then came the drought.

People from Clarke Creek mostly own or work on cattle stations, many run by extended and intergenerational family groups. School-aged children in the area were exposed to many impacts of Cyclone Debbie – from damage to community and family infrastructure, livestock and pet animal losses, to financial strain putting pressure on their families.

A problem-solving school

The saving grace of this community is the Clarke Creek State School (CCSS), which, in the absence of a township, serves as the community hub. It caters to the needs of 17 students from Kinder to Year 6, extends support to siblings, parents and extended families of those students, and provides a meeting place for all groups in the area, including the P&C Association.

The Clarke Creek P&C Association knew it was critical to support children through all this, and that school can help facilitate healing by providing the sense of normality that’s needed after a disaster. Since residents of Clarke Creek had to travel up to 230kms to access health and professional services, the P&C Association knew that, for help to be constructive, it would need to be brought into Clarke Creek.

The school had previously gained the services of a chaplain directly though the National Schools Chaplaincy Program, however the school could only afford one visit per fortnight without outside funding. By late 2018, it was clear that there was a need for ongoing disaster support for families. With so many pressures affecting the ability to fundraise locally in the tiny community, the P&C Association applied to FRRR’s In a Good Place program. A grant of $10,000 funded by CCI Giving essentially doubled the chaplain’s visits to weekly from July 2019 until March 2020, when the Department of Education funding applications opened.

Chaplaincy support proves vital

In small schools, the school chaplain is often the welfare provider, and plays a key part of the school support team.

The chaplaincy support at CCSS started shortly after the school and community were devastated by cyclone Debbie, and proved to be highly valuable to students, staff and the broader community, in their ongoing recovery and general mental health and wellbeing. The chaplain attends the school one day each week, working with the children in groups and one on one sessions. She provides emotional support and fosters leadership and kindness in the classroom, playground, and at school events.

“Chappy’, as she is fondly nicknamed, has been imparting those crucial life skills to the children and helping them to deal with the many challenges unique to living in a remote community in an isolated context.

It was a crucial time to bring in extra support, and the P&C Association don’t make light of the importance of Chappy’s role. Throughout COVID-19, the chaplain helped children deal with changes to their learning and became a central figure of stability for parents and the wider community.

The CCSS Principal notes how important the chaplain is in helping students transition through their education.

“I think the older students love the way she makes sure they all know that they have a voice and that someone cares enough to make the time to listen. She helped prepare older students for boarding school, and taught younger ones to be engaged in learning and practising kindness.”

The chaplain attends school and community events, and works with other schools in the cluster, thus creating support networks in the broader communities and creating an inclusive atmosphere and strengthened sense of community. But it’s the flow-on effects from the children’s gains that have the greatest power, as described in the final report:

“Our greatest achievement has been just stabilising our community. Oddly, this was really achieved through the children coming home from school with this positive energy and outlook from their time with Chappy, rather than working direct with parents and community. When the parents knew the kids would be ok and had someone strong to lean on, it was like a weight lifted and the school became the place of ‘normalcy and support’. Things picked up from there.

“In a small school and community, we have to stick together. Chappy has fostered this sense of belonging and caring in our children and it emanates from there.”

Located 1,000 km from Brisbane in the southwest of Queensland, Eromanga has a big claim to fame. The rural town, hidden deep in the outback of Australia, may only be 119 residents – but the biggest by far is Cooper, a 30 metre long and 6.5 metre high Dinosaur.

Eromanga is Australia’s furthest town from the ocean, and was drought declared for 13 years out of the 18 years to 2018. The many challenges brought on by a long drought, paired with the limited access to the town, have made increasing tourism a top priority for the local community.

Until recently, tourism around the region was almost non-existent, until the first dinosaur genus was found in 2004. From then, the Outback Gondwana Foundation founded the Eromanga Natural History Museum (ENHM), and since 2008 has been collecting and processing the fossils found in the area for locals, scientists and tourists to view.

The museum features fossils that have been preserved for more than 95 million years, however being located in a remote area has meant little foot traffic. Visitors faced long travel times to and from the museum, making day trips nearly impossible.

To overcome this obstacle, the Museum opened their own on-site accommodation, bringing more business to the area by allowing visitors to stay longer. Cooper’s Country Lodge offers four-star rooms, and thanks to a recent grant from FRRR, now has new kitchen and laundry facilities for their guests to enjoy.

The team at ENHM received a $20,000 grant through FRRR’s Tackling Tough Times Together program, funded by Australia Post, which allowed them to purchase equipment and fit out their onsite kitchen, laundry and support services. There is also a commercial kitchen featuring a microwave, griddle, deep fryer and new cookware, together with dining furniture and outdoor table & chairs.

The investment is already paying off. Despite the lockdowns and travel restrictions throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the popularity of the ENHM and Cooper’s Country Lodge has only increased, as Queenslanders have spent their holidays travelling in their own backyard. In 2020, the ENHM received the TripAdvisor Travellers Choice Award, meaning the Museum is in the top 10% of attractions worldwide.

The regional town of Emerald, situated in the Central Highlands Region of Queensland, is having a tough time. The area is experiencing a severe drought, which is having a significant impact on the town’s economy. However, there is a potential bright light for both locals and tourists in the new Emerald Arts, Culture and Technology Precinct (ACTP).

The precinct includes the regional library, art gallery, maker space, pottery, art pods and more. As part of the precinct, the Central Highlands Science Centre (CHSC) saw an opportunity to create a first-class science discovery and learning experience for kids in the local area, and tourists from out of town looking for a fun family activity. With the town experiencing a tough drought, keeping tourism going is important as it gives the town a much-needed boost to their economy.

A $18,700 grant from the Australian Government through our TTTT program meant that the organisers of the centre could work together with key community and tourism groups and conduct a feasibility study into the potential of establishing the centre as part of the Emerald ACTP. The feasibility study investigated the opportunities and measure of success or failure of the Centre to drive an economic benefit for CHSC and the wider region.

The project was found to be feasible, and the CHSC received further funding to help with their relocation costs. While the shift has been put on hold due to COVID-19, the bigger premises mean that the CHSC has been able to stay open and continue providing education opportunities and a tourist attraction for visitors from outside of town. It is excellent to see this project making such a big difference to the long-term sustainability of the centre.

Gai Sypher, who is the Coordinator of the CHSC, said of the project; “Drought is far reaching across Australia and the recent rain has only given hope. Drought is part of the Australian landscape. We need to invest in our rural communities to attract visitor who will spend money to boost our rural economy.”

“Thank you for this wonderful opportunity that has funded the feasibility study. We have actioned recommendations from the study and are scheduled for a relocation in June.”

Gai Sypher – CHSC Coordinator

Red Ridge Interior, a creative community organisation that provides opportunities for learning, connection and community in Queensland’s Central West, knows how hard it can be to tackle tough times. After being drought declared for six years, the townships of Winton, Longreach, Barcaldine and Blackall really needed a boost.

With the help of a $60,000 grant from the Tim Fairfax Foundation, and community partnerships with Central West Suicide Network, Winton Neighbourhood Centre, Blackall-Tambo Neighbourhood Centre, Longreach Art and Craft Centre, Royal Flying Doctor Service, Central West Hospital and Health Service, Central West Aboriginal Corporation and Queensland Health, Red Ridge Interior was able to hold 46 workshops and three community events in these drought-stricken areas.

Each town engaged in community wearable art workshops to make costumes that celebrated the unique materials, textures and landscape of their towns. A total of 33 costumes were created, with the collection being named ‘Beauty Within the Drought.’ These costumes were then worn by performers during three performances to mark the end of the project.

People were also given the opportunity to travel to Barcaldine to participate in make-up artistry workshops, meaning that performers also had access to local makeup artists. A dance troupe of 25 young people also participated in the performance and showcase of the costume collection.

Within every workshop, layers of physical relaxation, self-care and well-being activities were integrated for participants. These layers of integrated care were individually tailored to meet the needs of the local community. A combination of creative skills development, physical health and emotional wellbeing were important outcomes.

Events were incredibly well received by the community and the costume collection has gained ongoing and widespread interest, with a number of groups and gallery spaces enquiring about exhibiting them.

Louise Campbell, manager of the project, told FRRR this was such an amazing project that would not have achieved what it did without the FRRR grant and partner donor Tim Fairfax Family Foundation.

“The grant enabled us to deliver the best project possible that exceeded all expectations. An exhibition of garments is now hosted in the Grassland Gallery in Tambo and expected to travel across the region. Additional communities have expressed an interest in being involved in future projects of this nature.”

Storytelling is a vital part of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture, allowing beliefs and concepts to be passed on through generations. JUTE Theatre Company (JUTE) uses theatre performance and workshop participation to present professional role models and positive stories about a range of Indigenous experiences and possible futures.

Founded in Cairns in 1992, JUTE helps Indigenous students feel valued and connected, by letting them see their cultures and stories represented on stage. There are also longer-term benefits in employment and post-school options for young Indigenous people. Since the beginning of its Dare to Dream program, JUTE has impacted over 6,000 young people and community members in remote parts of North Queensland with more than 3,600 young people taking part in skills development workshops.

With the support of a $15,000 ANZ Seeds of Renewal grant, JUTE was able to take its 2019 show, The Longest Minute, to 10 North Queensland schools in Lockhart River, Bamaga, Mapoon, Mossman, Ravenshoe, Yarrabah, Mt Isa, Doomadgee and Cloncurry – all very remote locations with significant numbers of Indigenous students. The Longest Minute is a story about the 2015 National Rugby League Grand Final, won by local heroes, North Queensland Cowboys in a nail-biting finish.

The funding helped JUTE refine its school program to meet a broad range of needs across artists and facilitators, community, schools and students.

“It was fantastic,” said one of the Mapoon teachers. “The acting was incredible, and it offered our students an opportunity to see successful Indigenous people who are proud of their identity performing at their best. This is something we don’t have easy access to, being so remote.”